(datas of 2000 year, added thank to Christiane Thier-Rostaing)

(a bit “refreshed” with some more colour genetics in autumn 2010)

Gabriele Meissen

|

colors |

1996 |

1997 |

2000 |

Tot. |

% |

|

red/fawn |

101 |

73 |

87 |

261 |

44,84 |

|

sand |

63 |

50 |

82 |

195 |

33,51 |

|

brindle |

25 |

31 |

25 |

81 |

13,92 |

|

particolour |

9 |

9 |

14 |

32 |

4,50 |

|

blue |

1 |

– |

– |

1 |

0,17 |

|

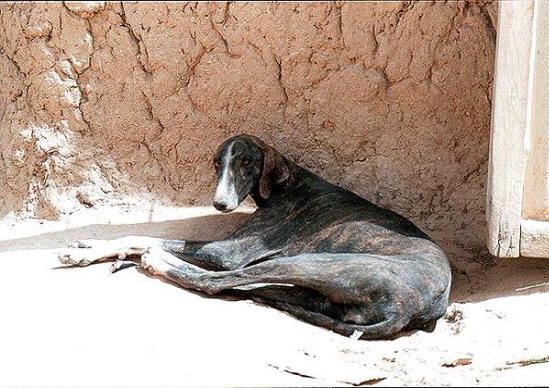

black |

1 |

– |

– |

1 |

0,17 |

|

cream |

3 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

1,37 |

|

lilac/silver |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0,52 |

|

Tot. |

204 |

165 |

213 |

582 |

100 |

It is clear that the data and statistics refer to a sample of the total population and consequently do not allow any definitive statements to be made as far as the exact numerical representation of each coat colour is concerned. Besides this fact, we weren’t able to visit some areas of the countries of origin, and our time was very limited, thus precluding any further research. Moreover, some of the rare specimens met during both of the two expeditions may have been considered twice. It is, however, possible to underline significant differences in the quantitative division of colours.

TAB.2: types of colours and patterns recorded in 1996, 1997 and 2000

|

pattern |

number |

% |

|

Black mask |

56 |

9,62 |

|

Grizzle/black and tan |

28 |

4,81 |

|

Black saddle |

24 |

4,12 |

|

Blue nuances |

14 |

2,41 |

|

Blaze |

75 |

12,89 |

|

White collar around the neck |

35 |

6,01 |

If we take into account that the colours and design recognised by the FCI standard are red, sand and, since 1994 black brindled, we can appreciate that there are certainly more colours than just those spread throughout the world. We can not hide the existence of these other colours, even if they are the less common ones, as our report represents.

Francis Roussel affirmed the presence of black and brindled specimens in his 1975 thesis, “Study on the South-Sahara Sighthound”. Ursula Arnold quotes the percentages of brindled (6%), black (2%) and chocolate (3%) specimens met during her travels in 1984, 1987 and 1988 in her article “The Azawakh in its Country of Origin”, in the magazine “Unsere Windhunde” (February’, 1989).

Similarly, in “Der Azawakh Windhund der Nomaden in Mali” (The Azawakh: the Nomads’ Sighthound in Mali) by Strassner and Eiles, there are 50 photos taken during their trips between 1986 and 1987 in the Azawakh Valley, between Menaka and Anderamboukane. Among them, there are five photos portraying pied specimens, one representing a cream dog and four showing black-manteled dogs.

Such a collection of distinctly different publications witnesses the presence of a variety of colours in the dog’s coat besides the most traditional ones listed in the FCI Standard, and the colours which are less common still represent the same variety in phenotype as the red, sand coloured or brindled specimens.

Such Azawakhs have, in fact, been detected in all the regions we visited, namely: Niger; Dalol Bosso between Banibangou and Tera, where the dogs are owned by the settled Haussa; Mali; the Azawakh Valley, between Menaka and Anderamboukane; as well as in the areas surrounding Ansongo and Gourma, by the Tuaregs camps. In each of these regions we found no differences in the distribution of coat colour varieties. This data basically runs counter to the thesis, otherwise spread so widely in Europe, that colours which are not mentioned in the Standard might belong only to specimens living on the threshold of the actual breed, and thus signify mongrel blood.

A set criterion should be followed to distinguish on a more scientific basis the range of colours found in the Azawakh, as some of the specimens catalogued as red, sand and brindled show a saddle covered with black hair, more or less solid, and some with even a full black coat, where the basic colour like red or sand is reduced to grizzle markings.

I have known many specimens coming from pure-bred European bloodlines who, once adult, showed a classic red coat even though they had been bi-colour when puppies, with a black saddle spread on a large part of the body, and who had shown no traces of sand or dark colour but for on the legs, under the tail and on the muzzle. In a matter of a few weeks, the bi-colour coat disappeared and left no traces other than a few dark hairs. In Mexico, in a litter coming from various ancestors (among which were a sand bitch imported from Mali, a red dog coming from Burkina Faso and a red dog bred in Yugoslavia from the first imported Azawakhs), many of the specimens kept their black coat through adulthood. Such specimens, as well as those who did not keep a black coat beyond the puppy phase, are genetically catalogued among the “agouti’ or A alleles (Ay and/or At).

For more detailed explanation about the colour genetic background of the most common coat colours in Azawakh read Sheila Schmutz´s chapters about fawn or clear sable (ay) and tricolour, black and tan, tan points (at), which was last updated on October 6, 2010

http://homepage.usask.ca/~schmutz/agouti.html

Referring to Sheila Schmutz´s study about Saluki coat colours, which was completed about the genes causing grizzle in spring 2010, there is a special gene, MC1R, which causes grizzle coloration. It is not ay, which I described above. So most probably the term grizzle used in this article to describe certain colours of the ay/at serie is not correct

http://homepage.usask.ca/~schmutz/SalukiColor.html

There is no scientific proof yet, if the grizzle coat colour exist in Azawakhs

grizzle ?

We should also add to the range of existing colours from those found on Azawakhs with diluted, blue nuances, blue noses and light eyes, and “grizzled” markings on the head, legs, breast, and under the tail. Such markings are, above all, present in the specimens classified as red/fawn/sable, sand and are mostly black, sometimes diluted to blue. They are even more evident in the young puppies. The contrast of colours in this type of coat is attenuated until it disappears more or less during the growth. In several recorded dogs, however, such markings can still be recognised in adults.

Among these, two of the specimens also show brindling. Azawakhs whose coat had the same colour as that of a Weimaraner were classified as silver/lilac in Table 1, and exhibited a pattern which could be defined as grizzle dilute brown (b/b at the brown locus). In other specimens defined as “cream” it is in fact a diluted red colour (e/e, which is cream to white); the lips, eyes and eyelids are very much less pigmented. One of the specimens classified as cream in our statistics also showed blue brindling.

Almost all of the specimens seen showed, as required by the F.C.I. standard, white markings on the legs, breast and tail. Two red Azawakhs had only a star on the breast. Several were missing the white tip on the tail. Conversely, the extension of white markings on the neck and collars were much more frequent than what we are used to seeing in Europe. We had the chance to see, more than once, white markings which reached the shoulder and the nape of the neck. Such variety in the distribution of white markings can be genetically explained by four alleles:

S surface is totally pigmented;

Si white markings are limited to the muzzle, forehead, breast, stomach, legs, and tip of the tail; (this is what the FCI standard wants)

Sp pied;

Sw pied with a predominance of white.

The Si allele is certainly the most commonly expressed allele in the Azawakh population, but we should not deny that Sp and Sw are an integrative part of the genetic pool of the breed, as this would explain how we took note of 18 pied specimens. Two of the specimens did not show pigmentation except on the head, eyelids and ears, and undoubtedly were carriers of the Sw allele with a predominance of white. It is impossible to develop in the space of one article the genetic heritage of white markings and we will consequently limit our study to the following descriptive diagram.

It is evident that the current standard, which requires white markings on the legs, breast and tail, and penalises their absence, tries to deny the full range of possible colours in the distribution of white markings in the Azawakh. Thus, the standard takes only the majority into account, excluding a large number of specimens it should not ignore, in order to emphasize the breed type found in Europe. This also holds true for the other colours and patterns which the standard does not recognise.

Notwithstanding the fact that this group of specimens exhibit colours and patterns which are not recognised by the standard, and represent a minority of the Azawakh population, we should however include them in the FCI standard. In fact, it is not right that a breed standard recognises but a portion of the colour varieties actually possible. It would be more appropriate for the standard to reflect the data gathered in the countries of origin, and to report them faithfully, as the Azawakh belongs to a strong, ancient breed, which has established its history and adapted itself to its environment. It is basic to maintaining the authenticity of the breed, because it is bound through the cultural patrimony of its country of origin. In Europe, fanciers should control breeding in order to avoid selection aiming at the production of a hyper-type suitable for the show ring; a trend clearly visible in the recent past concerning some eastern breeds. Of course, every standard is simply a the description of an ideal phenotype at a determined moment in time, and it is in no way immutable.

But, if acknowledgement concerning colour and markings remains too limited, genetic stock will be reduced unnecessarily, and consequently the risks linked to increasing genetic homogenity will rise. The most recent annual Azawakh Exhibition by the DWZRV (the German Sighthound Club), with 55 specimens shown, was an accurate mirror of the limited range of colours in the European population which, following an arbitrary selection aimed at a well defined type, no longer represents the multiplicity of colours which can be found in the countries of origin.

TAB.3: distribution of colours in the azawakh at the 1997 annual exhibition

|

Colori |

number |

% in the ring |

% found in country of origin |

|

Red/fawn |

38 |

69,10 |

44,84 |

|

Sand |

3 |

5,45 |

33,51 |

|

Brindle |

13 |

23,84 |

13,92 |

|

Cream |

1 |

1,81 |

1,37 |

|

Blaze |

3 |

5,45 |

12,89 |

|

white collar around the neck |

2 |

3,63 |

6,01 |

In order to safeguard the breed and its authenticity in the years to come, we can but hope that the variety and the genetic richness within the Azawakh population will rise, and this not only as colours are concerned.

Thanks to the integration of newly imported specimens to breeding programs, the problems linked to excessive inbreeding may be avoided or at least reduced. Moreover, a timely extension of the standard to include the full range of documented colours, as mentioned before, would be a progressive step toward greater genetic heterogeneity.

Epilogue

In order to sum up our data gathered during the last two expeditions of the ABIS, and to illustrate the general meaning of the present article, here is chart 4 concerning the specimens seen in 1996/97.

In 1997, we unfortunately recorded 39 dogs less than the year before. This can be explained by the fact that we had no available time to visit Niger, and that consequently only a very few Azawakh were entered in this study, with the exception of those met in transit from Anderamboukane to Tera, via Banibangou, Ouallam and Tillaberi. The regions we went through in Burkina Faso and Mali confirmed our previous results.

TAB. 4: division of azawakhs according to the origins of their owners

|

country |

nationality |

Number of dogs |

Tot. |

||

|

|

|

1996 |

1997 |

2000 |

|

|

Niger |

Haussa |

50 |

9 |

– |

59 |

|

|

Tuareg |

19 |

10 |

– |

29 |

|

|

Peulh |

– |

9 |

– |

9 |

|

|

Bella |

– |

3 |

– |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mali |

Haussa |

1 |

– |

4 |

5 |

|

|

Tuareg |

38 |

55 |

72 |

165 |

|

|

Peulh |

– |

– |

6 |

6 |

|

|

Bella |

5 |

– |

22 |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Burkina Faso |

Haussa |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

|

|

Tuareg |

6 |

8 |

18 |

32 |

|

|

Peulh |

21 |

31 |

20 |

72 |

|

|

Bella |

49 |

23 |

68 |

140 |

We spent more time in the Azawakh Valley, and we met more people there because of the return of the refugees, which gave us the opportunity to record more specimens. Table 5 gathers the Azawakh data according to phenotype, following the FCI standard’s criteria.

Some puppies are entered in Table 5’s category of “not classified” because of their young age.

We should also underscore that in 1997 settled people owned Azawakhs, and above all in the countries of origin. The great percentage of Tuareg in Mali can be explained by the fact that we met many nomad Tuareg in the area we went through in the Azawakh valley. Unfortunately, we still cannot report information about populations based in other regions of Mali, as they are domains which are regarded as “annexed” to the areas which are the cradle of the breed.

TAB.5: classification of the population according to the phenotypical criteria of the standard

|

|

1996 |

1997 |

2000 |

Tot. |

% |

|

Very typical |

85 |

75 |

91 |

251 |

43,13 |

|

typical |

18 |

50 |

72 |

207 |

35,56 |

|

Less typical |

18 |

8 |

17 |

43 |

7,39 |

|

Not classified |

16 |

32 |

33 |

81 |

13,92 |

|

Tot. |

|

|

|

582 |

100 |

|

Coarse tail |

18 |

11 |

36 |

65 |

11,17 |

|

Ear carriage incorrect |

6 |

13 |

39 |

58 |

9,97 |

|

Longer coat hair |

5 |

10 |

31 |

46 |

7,90 |

|

Curled tail |

7 |

6 |

9 |

22 |

3,78 |